Quantum Mechanics without the maths or philosophy

Previous Page

Point 8: Exchange symmetry.

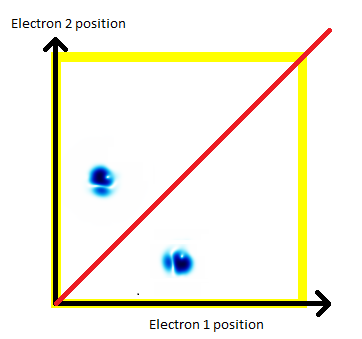

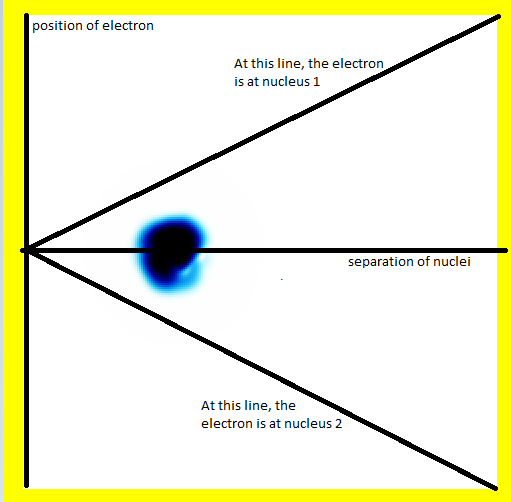

We have a problem. Our theory looks great, but it's wrong. The universe happens to have a symmetry that our picture doesn't. The universe actually looks like this:

There are several ways that you could think about this, but I'd suggest that it's as if there are a vast number of mirrors stretching across the universe. For every pair of electrons, there seems to be a perfect reflection. Every time I say that electron 1 is at position A, and electron 2 is at position B, it turns out that there's an alternate blob of probability with electron 1 at position B, and electron 2 at position A.

Imagine meeting a perfect twin. When you step to you left, they step to their right. If you take a step forward, you bump into them. No matter what you do, you can't squeeze past them, because you always bump into them.

A symmetry like this isn't a change to the Schrödinger equation. There's nothing in the Schrödinger equation that says that electrons have to have this symmetry. But what the Schrödinger equation does say is that if the electrons are perfectly balanced in this way today, the way they move (identically to each other), means that they will remain balanced. And it seems that the world is perfectly balanced in that way.

This symmetry is called the "exchange symmetry". It applies to every pair of identical particles: Pick an electron, pick another electron, and you'll find this "mirror" between them. If you pick a proton, and another proton, you also find it. If you pick an electron and a proton, though ... no mirror. It only applies to two identical particles.

And here's the real animation:

|  |

Summary:

Electrons in the universe have a perfect symmetry: The chances of any two electrons being at A and B is exactly the same as the chances of them being at B and A (and there's a phase relationship which we haven't mentioned).

In the animations we've got here, that shows up as a diagonal mirror symmetry.

Point 9: Spin

If we introduce quantum spin to the theory, we get a model that can predict the spectra, transition strengths, binding energies and thermodynamic properties of every atom and molecule that we know about. The accuracy is good for light elements, and less good as the elements get heavier.Here's an animation. It shows a single electron moving around a 1-dimensional enclosure. It is initially spin-up. There is a magnetic field applied to the right hand side of its enclosure (direction = out of the screen).

The electron oscillates between spin-up and spin-down.

Here's the animation:

You can see that the graph starts exactly as it did in the first few points. But now there are two graphs. Those represent spin-up probability and spin-down probability.

In the animation above, the electron is starts on the left. It is spin up (ie. on the top graph), and it is moving to the right. When it crosses into the area with a magnetic field, it is mostly converted to spin down: It appears in the bottom graph instead of top. In this enclosure, if the electron goes off the right hand side of the screen, it reappears on the left. The second time it passes through the magnetic field, it is partly converted back to spin up.

Summary

It's almost as if there are two types of electron, a spin-up electron and a spin-down electron. A magnetic field can convert an electron from spin up to spin down. In the diagrams here, that will look like electron probability moving from one graph to another - in this case from the top graph to the bottom graph.

Make sure you understand the following points:

- We now have two graphs instead of one. Each graph is the probability of finding the electron at that position in that spin state.

- A magnetic field can convert electrons from spin up to spin down and back.

Point 10: 1d helium.

We can bring this all together and simulate a 1-dimensional helium atom.There are four spin states for the electrons in helium: up-up, up-down, down-up, down-down. That means that we need four panels in the animation. Each panel is a different spin state for the electron pair.

If this was a full 3d model, rather than a 1d model, this would give the right vibrational levels for Helium. There are slight disagreements between theory and experiment, but they mostly seem to be explainable in terms of relativistic corrections.

This agreement between theory and experiment is not found in any competing theories - we do not know of any simpler theory that explains the energy levels of the Helium atom (plus the many, many other atomic properties that we can calculate using this theory) to a comparable accuracy. This provides very strong supporting evidence for quantum mechanics.

Point 11: 1d Hydrogen Molecule

So far, we've considered nuclei to be point particles that don't move. Quantum mechanics is meant to describe everything. To see how nuclei fit into the model, let's look at 1-dimensional H2+Let's not consider spin.

H2+, by the way, is the normal hydrogen molecule, with two nucleuses (each 1 proton), but missing an electron, so there's only one electron in play.

For 1-dimensional H2+, there are really three positions: the position of the electron, the position of nucleus 1, and the position of nucleus 2. So we have a 3-dimensional areana for the probability wave to move in. All the examples above were contrived so that we had either 1 or 2 positions in our model, resulting in 1- or 2-dimensional animations.

Luckily, we can use a trick to get H2+ more 2-D: We only consider two of the three positions:

- The position of the electron relative to the centre of mass.

- The distance apart between the two nuclei.

In this diagram, the electron is in the middle of the molecule (hence the probability being in the middle on the vertical axis). The nuclei are separated somewhat (hence the probability being not as far left as it could be).

Another diagram is the starting point for the next simulation:

This is the same, but the electron is now near nucleus 2. In effect, we have a neutral hydrogen atom based on nucleus 2, and a single proton: nucleus 1.

Avoid falling into the trap of thinking that the single proton is not being shown in the diagram, or that only the electron is being shown. The entire system: the two protons and the electron are all characterised by two positions, and these form the x and y axis ... everything going on in this collision is shown. The fact that there's less going on than you expected might even be a good thing.

Animation:

What's going on here?

- The electron starts on nucleus 2.

- The electron is initially both bound and unbound.

- This can be seen most clearly by the fact that some probability "explodes" in the vertical direction. That's the electron zipping away. However, after some of the probability density has "zipped away" (into 2 free protons and a free electron, which here simply leaves the simulation), there remains probability density mainly clustered around the electron being at nucleus 2. That probability density represents a bound hydrogen atom.

- This initial setup, both bound and unbound, is referred to as a superposition.

- The movement on the vertical axis is much faster than the movement on the horizontal axis because the electron is lighter and so moves faster.

- The animation has been sped up relative to the other simulations - otherwise the nuclear movement would be too slow to see.

- The nuclei are moving toward each other.

- The nuclei bounce, but end up far apart.

This didn't produce a bound hydrogen molecule because it had too much energy: There's no way to get rid of energy here, so if the nuclei start off far apart, they will always have enough energy to return to far apart.

Of course, we could start them off close together:

And that gives us our H2+ molecule! This one is in the ground electronic state - which is why the electron isn't moving around much (no vertical fluctuation), but the molecule isn't in its vibrational ground state - so there is right-left motion.

Summary

We can easily model molecules using this theory. Of course, as you add more electrons and more nuclei, the number of dimensions increases quickly: The true 3d Hydrogen-2 molecule has really got a 12 dimensional arena (3 dimensions times 4 particles) for the probability wave to move around in. Luckily, there are tricks that make it possible to make calculations to quite a high degree of accuracy anyway.

The most striking thing, though, is that the theory itself isn't all that complicated, and yet it gives us very accurate descriptions of atomic and molecular spectra, thermodynamic properties. It explains how electrons move in metals, in semiconductors (which helps us build transistors). The theory only seems to break down when we have very high speeds, when we knew it would break down anyway because relativity isn't built in to the theory.

At high speeds, we do have a theory for how things work - the dirac equation, field theories, etc., but they tend to be harder to do calculations on, and they're outside the scope of this article.

Point 12: What are photons?

Actually, this is a topic for another day. Photons are another level of difficult, for the simple reason that their number can change - and in fact the number of photons is rarely well defined. Just as you'll have had to accept that the position of an electron isn't all that well defined, for most light, the number of photons isn't well defined.Although what a photon is seems central to quantum mechanics, second quantisation, as the mathematical process that defines them, is normally taught to physicists either late - or optionally - in the degree, or when they are graduates. So it's quite reasonable to feel that you more-or-less *get* quantum mechanics without understanding how photons work. It turns out, though, that although the maths is more complicated, and the animations would be a lot more complicated, the essential behaviour is similar anyway.

Summary

I've tried to present most of an undergraduate physics course in quantum mechanics using just animations instead of equations. There will undoubtably be parts that don't make sense, and there is a lot of detail that you can't get without the maths. But hopefully this introduction will give more understanding of what quantum mechanics actually is and says than the hundreds of articles that mainly enumerate "weirdnesses" that quantum mechanics has. I think understanding the Schrödinger equation is much closer to understanding quantum mechanics than understanding that quantum mechanics entails quantum tunneling, things popping into existence, wave-particle duality, or the inevitable (and philosophically important) multiple universes interpretations.More?

There's an article about how to make these simulations here.

© Hugo2015. Session @sessionNumber